What has become of the profession that we call graphic design? What was once an anonymous intersection between art and industry that pushed for higher ideologies outside of the occupation has become a passive tool for targeted advertising fueled by venture capital, obsessed with the creators and less so the work. This current climate is due to a number of systematic and societal issues that exist inside and outside of design. And in order to improve this, we need to examine some core problems: graphic design’s unwillingness to examine its societal implications, the profession’s obsession with personality and itself, and the lack of inclusion in design’s history and in the current discipline. By examining and outlining these issues, we can start to try and map a better future for our field.

Ethical Design Under Capitalism

(There is no Such Thing)

(There is no Such Thing)

One of the biggest faults of the professional discourse—discussions of graphic design in academia and online—is the failure to examine the real-world ramifications of the profession thoughtfully. To try and reverse this, I want to dissect and shine a light on the impacts of the practice on the real world. One of the explicit effects of branding, one of the core tenets of graphic design, is that it can elevate products without outlining their true implications. A change of font in a logo can increase the worth of the product it’s selling, but it can also deny access from people who may need it or trick people into thinking it’s something it’s not. For example, a simple SUPREME logo on a plain white T-shirt can significantly increase the product’s perceived value despite being manufactured in the same sweatshops as any other shirt sold at a big-box store. The only difference is the presence of graphic design, which signifies access to the luxury skateboarding culture that SUPREME has come to represent. With minimal design—a single logo mimicking Barbara Kruger’s anti-capitalist art style set in white Futura text on a red background—and some strategic cool-kid signaling, SUPREME manages to transform cheaply made everyday clothing and gentrify the grassroots culture of skateboarding into luxury fashion. Design can signify meaning—in this case, reinforcing the idea that all edgy skateboarders should wear SUPREME—an association that can then be exploited for profit.

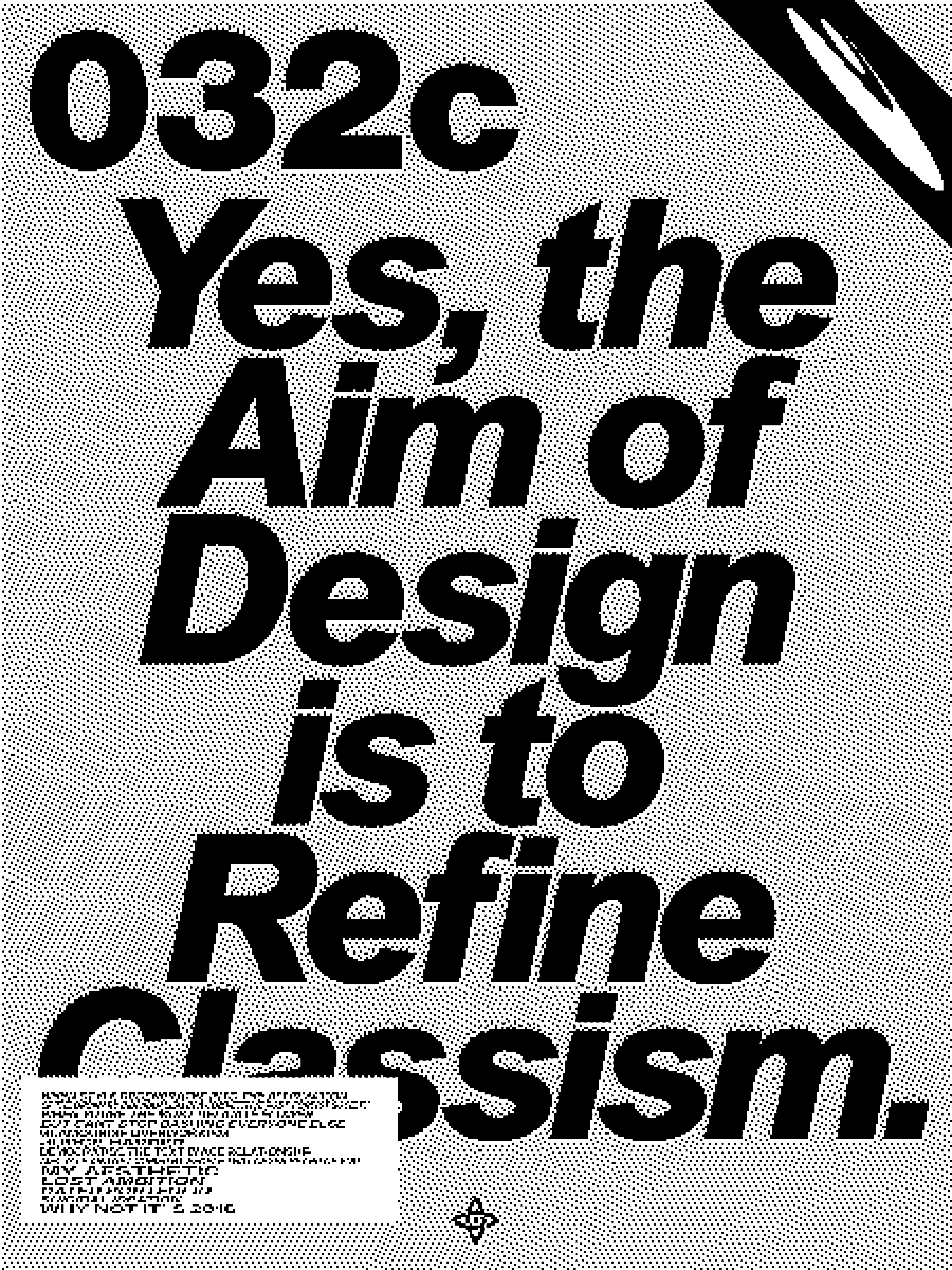

Michael Oswell, 2018

Oftentimes, we tend to obsess over aesthetics instead of the political implications of what we create and whom we create it. When a major rebrand occurs—Walmart, Jaguar1, and Burger King2 to name a few—the conversation is often dominated by discussions of font choices, aesthetic trends, or even designers creating their own version of a rebrand without context or process. We see less discussion about the meaning behind these rebrands, as companies typically redesign their visual identity when they seek a new public perception or when sales are lagging.

Within the design community, there is little to no discourse about what these companies truly represent and why they even need a rebrand in the first place. The meaning behind the aesthetics we design should always be critically analyzed, and we must consider who these companies serve and what their work signifies. Understanding your audience is one of the core tenets of graphic design, and knowing who our clients are—and who benefits from our work—should be essential.

Within the design community, there is little to no discourse about what these companies truly represent and why they even need a rebrand in the first place. The meaning behind the aesthetics we design should always be critically analyzed, and we must consider who these companies serve and what their work signifies. Understanding your audience is one of the core tenets of graphic design, and knowing who our clients are—and who benefits from our work—should be essential.

Designer unknown, 2017

Oftentimes, if graphic designers feel a sense of civic duty (or want us to think that they do), they launch fundraising campaigns, often with items like tote bags, enamel pins, or posters. While fundraising is undoubtedly valuable and graphic design can help raise awareness for a cause, volunteer work is even more essential3 as the number of donors and volunteers in nonprofit organizations continues to decline, even as total funding for the nonprofit sector increases. Civic engagement in a local community could go miles farther without perpetuating consumerism and contributing to the notion of designer-as-celebrity. However, existing under capitalism can feel like an inescapable restraint; individuals have different financial and personal needs, and some may not have the time for volunteer work or fundraising. Working in an industry such as advertising (with all its damaging influence) can be a means to an end. Not everyone has the allowance or desire to examine and counteract the systems they are forced into. Outside forces such as the broken healthcare system in the United States, make it extremely difficult for individuals to be completely independent of corporations. The options for many designers burdened with student debt can feel bleak, and most jobs in the field don’t give designers much agency. To try and counter this, graphic designers need to inform themselves about more than just aesthetics and consider the politics of who and what they are designing for. When the drones start flying over our heads, are we going to sit back and comment on the logos on the bombs? We need to do better.

DESIGNER AS CELEB

In Western graphic design, current practitioners can be divided into two eras: the pre-internet guard of professionals and the new crop raised on social media. In the popular 2007 documentary Helvetica, modernist designers such as Massimo Vignelli and Wim Crouwel were pitted against designers who became canonized in the 1990s such as Stefan Sagmeister and Paula Scher. With Modernism increasingly becoming an aesthetic or nostalgic design choice instead of a philosophical one, these personalities who rallied against modernist “objectivity” and proposed a more personal route of design began to loom high over the profession’s discourse. The argument of making design more personal morphed into a narcissistic view of our profession where the personality came first, and the work came second. Practitioners traded in their Wacom pens for gamer headsets, posters were replaced with TED Talks, typographic education with social media training. What was once positioned as a championing of expression over Modernism somehow morphed into celebrity worship.

Design blogs, conferences, and competitions all have catalyzed this climate of designer-as-celebrity. Placements on design blogs are often seen as a signifier of success rather than less tangible professional and personal gains. While blogs have made it much easier for designers to get better clients and be seen by art directors—practically making the old guard of award-show books obsolete—their rapid publishing pace can feel disposable. While a splashy write-up can be treated as the final crumbling step in the ladder of a career, it doesn’t satisfy the online craving for a bottomless pit of content.

Design conferences can help educate designers and connect them to the community, but increasingly they promote designers’ personalities instead of their work. They tend to be expensive and hard to attend unless a corporation is footing the bill, and presentations often take more cues from motivational speakers than from educational institutions. Good design lectures tend to balance real-world experience with educational theory. If a lecture veers too far in either direction, it can risk coming across as a basic portfolio showcase or an overly verbose presentation that is out of touch with reality. The best lectures combine both while managing to engage the audience, a skill that doesn’t always come naturally to working graphic designers. While a designer’s endgame may vary depending on their individual goals and interests, I would like to see graphic designers focus their time on making great work rather than promoting their personal brand via flashy lectures. Design conferences need to prioritize serving designers who are looking to expand their network and knowledge of design by presenting new and underrepresented voices rather than presenting empty (and often recycled) attempts at inspiration.

Design blogs, conferences, and competitions all have catalyzed this climate of designer-as-celebrity. Placements on design blogs are often seen as a signifier of success rather than less tangible professional and personal gains. While blogs have made it much easier for designers to get better clients and be seen by art directors—practically making the old guard of award-show books obsolete—their rapid publishing pace can feel disposable. While a splashy write-up can be treated as the final crumbling step in the ladder of a career, it doesn’t satisfy the online craving for a bottomless pit of content.

Design conferences can help educate designers and connect them to the community, but increasingly they promote designers’ personalities instead of their work. They tend to be expensive and hard to attend unless a corporation is footing the bill, and presentations often take more cues from motivational speakers than from educational institutions. Good design lectures tend to balance real-world experience with educational theory. If a lecture veers too far in either direction, it can risk coming across as a basic portfolio showcase or an overly verbose presentation that is out of touch with reality. The best lectures combine both while managing to engage the audience, a skill that doesn’t always come naturally to working graphic designers. While a designer’s endgame may vary depending on their individual goals and interests, I would like to see graphic designers focus their time on making great work rather than promoting their personal brand via flashy lectures. Design conferences need to prioritize serving designers who are looking to expand their network and knowledge of design by presenting new and underrepresented voices rather than presenting empty (and often recycled) attempts at inspiration.

Desmond Wong, 2018

Competitions like Young Guns help promote the idea of designer-as-celebrity—propping up well-lit headshots and charging over $200 entrance fees—while further diminishing the designer- as-designer. These awards prey on the dream of youthful success and often promote the same handful of designers and studios while setting up an environment that discourages those without the financial means to enter. Some competitions do have a historic function, showing how the tastes in design have shifted over the years, and some can be a stepping stone to acquiring better jobs or clients; however, such opportunities have dwindled over the years with the rise of social media. But as more competitions pop up, designers need to examine how competitions benefit them before committing their time and money. Seemingly, professional design organizations use competitions and conferences to fund their own institutions and initiatives, therefore birthing an endless feedback loop of competitions. To imagine and implement a new model, these organizations need to examine the negative effects their systems and practices have on the design industry at large and find productive ways to better support the community they rely on for their success.

Jennifer Daniel, 2017

THE DESIGN BUBBLE

There is no shortage of graphic designers these days who push forward aesthetics and design philosophy. It can be disheartening to see some of these skilled practitioners lost in the deluge of social media personalities and outdated design ideals. More followers on Instagram does not mean a designer’s work is good; it just means that they are good at playing the game of Instagram and the larger game of self-promotion. The most important step that we must take to improve this is to make the current and future generations more critical and inclusive. The systemic and structural bias that exists in our society also affects our profession. In 2014, designer Silas Munro wrote,4 “Yes, there are many great Black and brown designers in practice, but they had to work harder than their peers to get there. There were fewer possibility models, at least that has been my experience. My teachers, as talented as they were, didn’t reflect that aspect of my identity. My design history courses didn’t either. The monographs of design greats didn’t either. There are still so many gaps.”At every level of the workplace—and in design schools and publications—and if you have the means, you should absolutely support diverse voices. If designers have financial stability and an interest in helping others, they should try and lend their services to public works, government agencies, local communities, civic groups, and other systems that are less aligned with capitalism. While taking on work that is less financially rewarding can seem like a step backward, it can ultimately be more beneficial to the designer and society in the long run. And, of course, one can choose to work full-time for clients, institutions, and organizations whose end goal isn’t always about profit. The bottom line is if you have a voice in the field, it is your responsibility to speak up and attempt to map out a better future.

END QUOTES

Now is the time to dismantle the old guard and make way for a new generation of design. Graphic design can define our visual landscape, influence culture, and improve products and experiences for people, but we need to address the issues of politics and prejudice in our profession and start combating them. Design should no longer be defined as a battle between personal style, concept-based design, and objectivity as those arguments are already being made in the work. Graphic design must evolve, or else we’ll all end up in the bin.

An earlier version of this essay,5 edited by Ryan Gerald Nelson, Emmet Byrne, Paul Schmelzer, and C.C., was published on the Walker Art Center’s former design blog, The Gradient, on June 7, 2018.