The term “graphic design” is often said to have made its debut in the 1922 essay by W.A. Dwiggins, “New Kind of Printing Calls for New Design.”* In the essay, he distinguishes three categories of printing: plain printing, printing as fine art, and a third kind intended for advertising. This third type of printing, characterized by its widespread distribution and role in marketing, led to the creation of art departments within printing companies, essentially birthing a new profession:

“If all the talk about the importance of art to the industries of a nation is anything but buncombe it is of the highest importance that the advertising draughtsmen be made conscious of their influence and of their opportunity. Art will not occur in the industries until our fellow citizens learn to know the real thing when they see it. Advertising artists are now their only teachers. Advertising design is the only form of graphic design that gets home to everybody.”

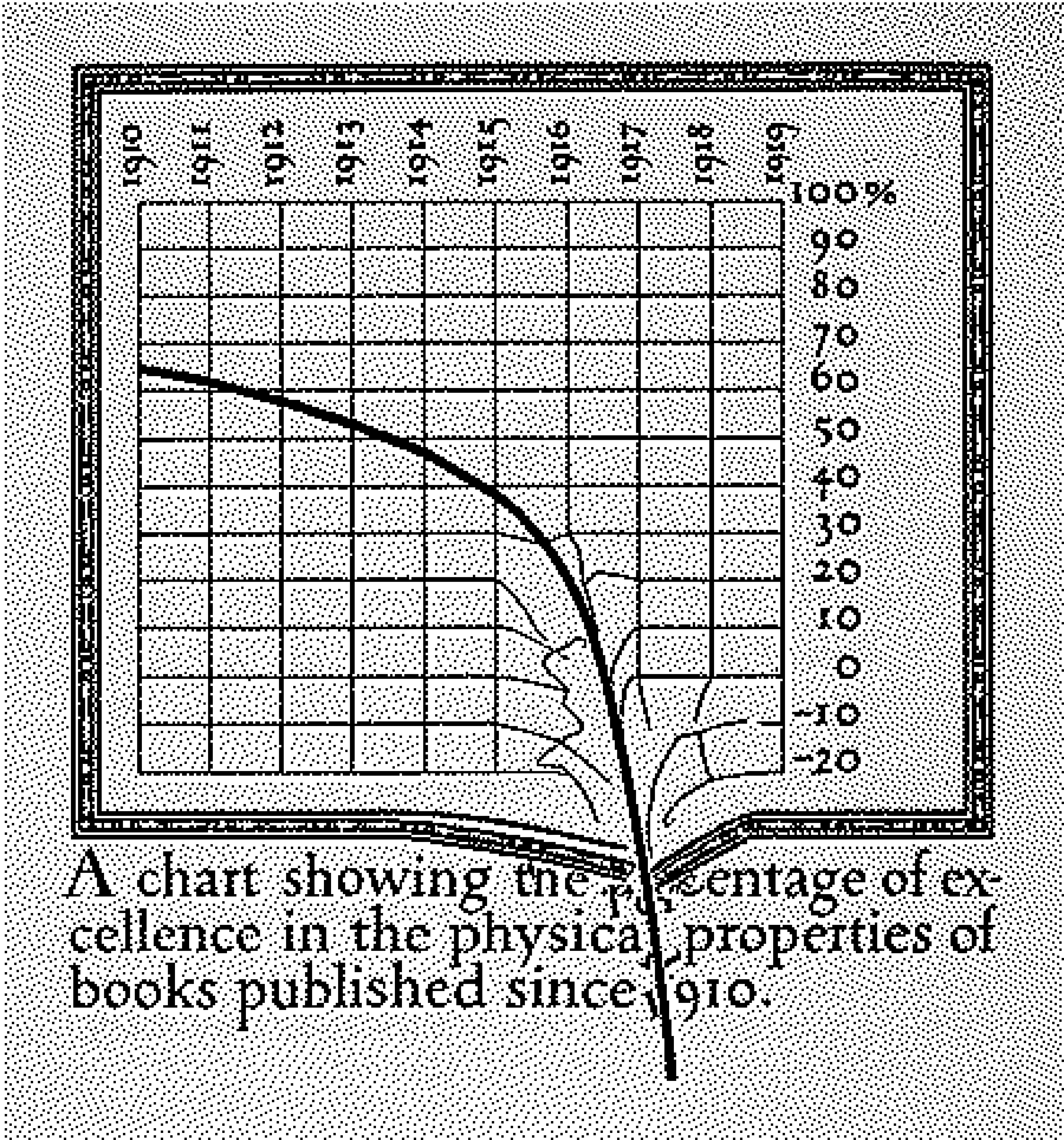

Now, this was not an essay about a new profession titled “graphic design,” but more so a warning of what was to come, the degradation of the printed arts due to capitalism:

“These artists, however, sound as artists they may be in themselves, are under a pressure from outside that is almost bound to make them unfit as exponents of sound standards.”1

W.A. Dwiggins, 1919

Dwiggins knew then of the power of the advertising arts and its burgeoning role in society, and the dangers of it eroding into mindless mush for the masses. The fact that the term “graphic design” was essentially invented here was merely a happy accident.

Over the course of this book, I aim to redefine the term “graphic design” for this moment, over a hundred years after Dwiggins published his essay. This definition, by definition, will be imperfect, pluralist and contradictory. Graphic design is not a static practice; it morphs with culture and marches forward with technology. It is not something that can easily be pinned down, and this book aims to be just as slippery—a collection of essays new and old, with the only throughline being a critical examination of the practice at hand. As it stands now, graphic design is rotted with leeches—some not specific to the field—as everywhere you look there are social media snake oil salesmen selling false dreams through cut corners and gamified algorithms, with AI looming on the horizon, threatening to destroy the practice entirely. But it is also plagued with its own specific ills, including endless presentation decks built by predatory subscription fee software on the backs of overworked art school interns burdened by debt. Through these essays, I hope to pull back the curtain on the issues plaguing the industry in an effort to collectively overcome them and usher in a new era of this practice that I love deeply.

The problems addressed in this book are not the fault of the single designer working for the ad-man or charity but rather the system. By examining and challenging these issues, I hope to offer a marching ant dotted outline for how the collective design community can overcome them or, at the very least, question their existence. With the likelihood of the next mass extinction event on the horizon, I want to state that graphic design is important, no less so than architecture or the other cogs that run the machine of capitalism, perpetuating these ills. I intend for the texts and ideas presented in this book to be seen not as an airing of grievances but as a potential solution to an industry-wide dilemma. Join me, and together, let’s design harder.

* Though the term appeared on syllabi and elsewhere prior to the article being published.

Over the course of this book, I aim to redefine the term “graphic design” for this moment, over a hundred years after Dwiggins published his essay. This definition, by definition, will be imperfect, pluralist and contradictory. Graphic design is not a static practice; it morphs with culture and marches forward with technology. It is not something that can easily be pinned down, and this book aims to be just as slippery—a collection of essays new and old, with the only throughline being a critical examination of the practice at hand. As it stands now, graphic design is rotted with leeches—some not specific to the field—as everywhere you look there are social media snake oil salesmen selling false dreams through cut corners and gamified algorithms, with AI looming on the horizon, threatening to destroy the practice entirely. But it is also plagued with its own specific ills, including endless presentation decks built by predatory subscription fee software on the backs of overworked art school interns burdened by debt. Through these essays, I hope to pull back the curtain on the issues plaguing the industry in an effort to collectively overcome them and usher in a new era of this practice that I love deeply.

The problems addressed in this book are not the fault of the single designer working for the ad-man or charity but rather the system. By examining and challenging these issues, I hope to offer a marching ant dotted outline for how the collective design community can overcome them or, at the very least, question their existence. With the likelihood of the next mass extinction event on the horizon, I want to state that graphic design is important, no less so than architecture or the other cogs that run the machine of capitalism, perpetuating these ills. I intend for the texts and ideas presented in this book to be seen not as an airing of grievances but as a potential solution to an industry-wide dilemma. Join me, and together, let’s design harder.

* Though the term appeared on syllabi and elsewhere prior to the article being published.